May 22,2022

Version 2 (August 24, 2022)

Dear Grandmother Sarah,

I recently wrote a letter to your grandfather, Henry Taber, my 3rd great grandfather, and the father of your mother Abby Taber. Very recently I found some interesting information I hadn’t known about our family’s much longer-term connection to Little Compton. You may well have known it and I will get to that in a bit. But first, the naming conventions of the colonists and early Americans have long fascinated me and your name is a very good place to start, incorporating as it does pieces pointing to the extended family’s past and interconnections.

At birth, you were named Sarah Gordon Hunt, carrying the name of Sarah Marsh Gordon who was the first wife of your father, John Hunt. Sarah was a cousin of your mother, Abby Taber. Your name—birth plus married name—Sarah Gordon Hunt Snow, points to three specific ancestors. The name Gordon in this country extends back to Alexander Gordon who was born in Aberdeen, Scotland in 1635 of the Highlands family that was loyal to the cause of the Stewarts. Taken prisoner of war when he and his family supported the Stuarts, he was subsequently released to Capt. John Allen of Charlestown, MA (today a neighborhood of Boston) on the condition he emigrate to North America [1]. Two of his descendants, sisters Abigail and Sally Gordon, married your grandfather and you are descended from the first wife, Abigail Gordon, who died a month after the birth of her third child. Henry married Sally Gordon a year later. And the name Gordon echoes through our family lines, not only as a surname but also as a first or middle name. Your married name of Snow goes back to Nicholas Snow who married Constance Hopkins who arrived on the Mayflower with her father and family. And, finally, the Hunt name was from your father and goes back to Bartholomew Hunt, born and married in England, where his first son, another Bartholomew, was born. It appears that all three arrived on North American shores in 1654 [2]. The third generation Hunt, another Bartholomew, was born in 1654 in Newport RI and died in Little Compton, RI in 1718 as, it appears, so did his father, in 1718. Subsequent Hunts, William (1703-1770), John (1739-1788), William (1758-1815), and Benjamin (1784-1859), were born and died in Little Compton.

And then came your father, John Hunt, son of Benjamin, born in Little Compton in 1813 and dying in 1862 in Minneapolis where he had gone to recover, he hoped, from what was called consumption and we know today as tuberculosis.

Your father, as you learned, left Little Compton as a young man, and found a position as a clerk for Henry Taber (your grandfather and my 3rd great grandfather) and was soon admitted into a partnership with Henry and his son, William Gordon Taber. More on the family is detailed in my book on the photo album your mother compiled in the 1860s [3, pp. 44-46]. Your mother ‘read’ the album to your daughter Agatha, who—in the early 1940s, probably soon after your death and the death of your daughter, Agatha’s sister, Edith—penciled in the stories Abby shared with her. The act probably comforted her at this time of loss yet sharing these stories in the album can also be seen as an important act of a family archivist, although she might not have thought it that way. At that time, it more likely was a way in the time of death to go back to a much earlier time when Abby told a very young Agatha, stories about the family. And Agatha’s 1912 sketch book, studied and presented in [4], led me to our ancestor Philip Delano, whose entrance into the family in the 17th century will be discussed in a letter to him. Agatha recorded seeing a descendant of his, Delano Whistler, on her travels in 1912, and this led to placing our ancestor, Philip Delano, securely into the family tree.

Returning to naming conventions, your daughter Constance, following Abby’s lead, similarly named her children (first and middle names) reflecting family connections—her first-born, a son, was named after her husband, Arthur; her second-born, my mother, was named mother’s brother Peter and the Hunt name. My middle name originally was Fay but after hearing for years from my mother that she wished she had given me the middle name of Snow, I legally changed it and am very pleased I did.

Family Archivists

Many more naming conventions are carried in our extended family tree one set of which I outlined years ago—the middle names of the daughters of Loum Snow and Abby Harris Easton Mowry [5]. As a teenager studying the family tree, I found those seven names magical, and visualized them as beads on a chain. Although when I wrote the article cited, I was missing the connection of the middle name for Jennie Sherson Snow, I later discovered that it was the maiden name of one of Abby’s brother’s wives. The two sons of Abby, Loum and Robert, the latter whom you married, were given no middle names. For your own reasons, none of your three daughters and one son (Constance, Agatha, Edith, and Robert) were given middle names. Perhaps you believed that with your intense work on family matters, which was well documented, there was less need to capture family ties through naming conventions. Unfortunately, your reasons were something you didn’t document. How your fierce interest in preserving family information has been transformed as I build an extended family tree, as comprehensive as records allow. You would have delighted in this detailed look at our family beginning with those who arrived in the 17th century. And as I am sure you are well aware, women have been the backbone to the preservation of family records. Before I turn to what you and subsequently your niece Deborah did to preserve records, let’s review a couple things from François Weil’s very useful book, A History of Genealogy in America [6].

Weil wrote [p. 29], “In colonial America …Kin-related genealogical consciousness was linked to changes in the conception of the family and to the growth of family and individual consciousness of the time.” He continues, [p. 35], “As they were transmitted from one generation to the next, family records of all types [furniture, pottery, portraits, needlework] took on added psychological and affective significance during the eighteenth century. They remained oriented toward posterity but also served as markers of remembrance and genealogical memory of early keepers.” He continues, broadening the scope [p.43], “As the nation matured and as pride in its origin grew, pedigrees also helped Americans to understand their local and national history … while reinforcing many Americans’ sense of self as individuals and citizens.”

Weil continues [p. 48] “During the colonial era genealogical representations had been an upper class preserve; by the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries middling New Englanders revealed an intense genealogical self-consciousness.” And Weil adds [p. 52] “Members of one group of Americans, however, were often “genealogists constitutionally”: women. Their role as stewards of family memory grew in the revolutionary and postrevolutionary decades as the ideology of republicanism placed them at center stage. The training of women as stewards of family memory began as a young age.”

Sarah, you were a major force in the family history, compiling a number of journals of family records including family small objects and furniture. In one such journal you documented pieces that the Russells gave to your daughter Isabel, giving us the only record found to date, that Isabel was betrothed to their son, who died in Brazil. That marriage would have brought together two strong whaling and shipping families, but it was not to be. Their son, as many other New Bedford sons and often families, moved to Pernambuco to work in their family businesses connected to those of Humphrey Hathaway Swift, whose work will be covered in a letter to him. Unfortunately, as of now we know nothing more of the Russell son’s death.

Your granddaughter, Deborah Snow Simonds, daughter of your son Robert, picked up the mantle of family chronicler and was so delighted to share information, stories and documents with me when I returned from three years in the Mideast and finally sat down to study the family in earnest. She had followed your lead and I hope to continue my research and convince some others in the family to take up the cause. And while celebrate both your and Deborah’s work in collecting, retaining, and sharing family history, we cannot neglect the efforts of your mother, Abby Taber Hunt, whose creation of the family album and her stories to Agatha as a child, offer more on the family and its neighborhood that had been gathered. As I wrote in the preface [3, xiv]:

“One could argue that this narrative is only of interest to family. Rather, it can be seen as one example of petite histoire, the account of particular households and neighborhoods. And, beyond that, the narrative opens a window from a personal point (the extended family, neighbors, and other townsfolk) to the city at large in the mid-nineteenth-century, a city with abundant prosperity based on whaling and developing textile mills, and a city at the forefront of the abolitionist movement.”

Turning to information came to me recently that changes my mistaken idea that the family’s relationship with Little Compton was introduced through John Hunt and his older brother Otis, Otis bequeathing the family house in Little Compton to you and Robert [3, p. 43]. You and I and so many others can trace our roots in part to two Mayflower passengers—John Alden who was hired as a carpenter and Priscilla Mullins who accompanied her parents (William and Alice, her brother, Joseph, and family servant Robert Carter) on the ship. That brutal first winter took all them except for Priscilla. John and Priscilla married and produced 10 children one of whom, Elizabeth, married John Pabodie, born in England in 1620. Their children were born in Duxbury and when all but one had married they moved to Little Compton where John served several roles in town and Elizabeth was honored with an impressive grave commemoration in the Commons burial grounds much later; she was also considered the first white female born in the Plymouth colony [7]. So, in short, the roots in Little Compton extended to some of our earliest ancestors. And then along came your father John who moved to New Bedford and now you and I and many others can trace roots to both Little Compton (Hunts, Wilbours, and Peckhams to name a few families) and New Bedford, years before Otis Hunt bequeathed the Little Compton house to you.

Before turning to specifics of war service of some of our ancestors—limited in this letter to late 18th into the 19th century—it is useful to consider a point specific to New Bedford and one to women in the American revolution. In the first instance, as discussed in Our County and Its People [8, p. 327]:

“In the two wars [the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812], which seriously affected Bristol County, the Quakers were uncompromising in their attitude of non-resistance … and it was due to their influence that Old Dartmouth was frequently under rebuke of the court for negligence in military matters. Many cases of arrest and imprisonment are recorded for refusal to enter military service. Their loyalty to their religion caused them much loss of property and distress during the Revolution, besides frequently leading to charges of actual disloyalty to the American cause. For such charges there was no ground whatever; if the Quakers would not fight, they at least hoped for the triumph of the colonies. In times of peace their influence was ever exerted for the religious moral, and educational welfare of the community.”

From Franklin Howland on the history of Acushnet [9, p. 63-64], we move beyond the issue of military service and receive reports on the inhabitants including women.

“The inhabitants of the Acushnet section of the town resolutely resolved that, “survive or perish,” they were determined to be American Patriots from the beginning of the struggle for liberty till its close. The women of Acushnet were in the vanguard and joined the men in the first show of resistance by refusing to drink tea, which every patriot declared to be unjustly taxed. Encouraged by the total abstinence movement, the men had an article of inserted in the warrant for a town meeting July 18, 1774.”

This article to prevent the use of tea was passed as well as a subsequent one to boycott all articles manufactured in Great Britain and Ireland.

When turning from the specifics of Acushnet to a study of the first generations of women in colonial America, we read in [10, 174] that by the 1770s

women had been mulling over the political events of the era in their diaries and letters for several years. Furthermore, free colonial women expressed a clear understanding that their economic decisions—what to buy, what to declare a necessity, what to eschew—had become political decisions. This political awareness was dynamic, growing stronger and more widespread over the decade between the Stamp Act and the Declaration on Independence. [10, p. 174] … As the likelihood of war grew stronger, women’s activism increased. In New England, where fighting preceded a formal declaration of war, observers on both sides remarked on women’s enthusiasm for conflict. … The women, recorded one eyewitness, “surpassed the Men for Eagerness & Spirit in the Defense of the Liberty by Arms.” [10, p. 178]

And finally, in [10, p. 189 ] we read that

Some women found other ways to serve the military. A few set aside their society’s gender boundaries completely, donning men’s clothing—assuming a male identity—to enlist in the American Army. The most famous of these women, Deborah Sampson Gannett, saw active service as Robert Shirtliffe until she was revealed as a woman by a physician attending to her fever. How many other white women saw battle as men is unknown. … A significant number of women chose to use their society’s gender-based assumptions to advance the cause they supported. As spies and saboteurs, some women used their femininity as a disguise to gather intelligence and convey sensitive information. Their stories are numerous and frequently told.

A denouement similar to Shirtliffe’s of a sailor on a whaling ship in the mid-19th century is known from papers written by one of the owner of the ship to the Attorney General of the United States showing his fury that they had been charged $300 for her care when she was turned over to the American consul in Peru—the standard charge for a man was $36. As this whaling ship vignette, recounted in the discussion of the ship’s Capt. Thomas Sullivan [3, pp. 61-62], suggests, women also took on a male persona for adventure perhaps or to earn money.

Barely 220 miles west of New Bedford, we find a young Quaker woman, Hannah Lawrence, whose family traced its origins in New York back to early 1600s Long Island. In Manhattan she was seen—by a Loyalist military officer, Jacob Schieffelin, a son of German immigrants—disseminating incendiary poetry against the British occupation under her pen name “Matilda.” She personally distributed some of her missives in front of Trinity Church. Jacob Schieffelin was billeted in her family’s house by August 9, 1780, soon after first seeing her and a month after he reached Manhattan. Hannah and Jacob were married on August 13, 1780, and soon departed to spend the war in Canada. After the end of the Revolution, they became pillars of Manhattan society as Jacob moved vigorously into commerce and real estate speculation wherever he found himself [10].

While none of these actions by women is any surprise to us today, having read of so many holding such roles in early and later wars around the world, it is pleasing to see our female ancestors and neighbors strongly participating in the Revolutionary War.

Returning to the Gordon family, whose name likes many others echoes in our extended family, we see that the first Gordon of our line in this country fought in the war on the Stuarts’ side in the 1600s and was captured. Alexander Gordon (born in 1635 in Aberdeen, Aberdeen, Scotland) arrived in New Hampshire by 1660 when he married Mary Lysson (born in 1639 in Daviot, Aberdeenshire, Scotland). More on Alexander and his descendants can be found in [1]. We see a clear line from him to his fourth great grandson, your great grandfather, William Gordon (1754-1835) who served in the Revolutionary War and subsequently in the War of 1812. Since so many of our ancestors were Quakers, it is useful to to present the Methodist Gordons and their war service; in another letter to an earlier ancestor, I’ll touch on war service of some of our ancestors in the colonial wars. As a Methodist, William Gordon and family displayed a fluidity in religions that has been discussed about New Bedford in general [3, pp. 30-34]. His three daughters from his second marriage to Abigail Pope all married Quakers—Betsey to Thomas Wood; and both Abigail and subsequently, after Abigail’s death, Sally to Henry Taber [3, pp. 51-55].

Revolutionary War and New Bedford and Its Neighbors

As those who have even passing acquaintance with the Revolutionary War know, the battle of Lexington—where the shot heard around the world was fired—was fought on April 19, 1775. It was a battle whose primary significance was the beginning of eight years of this war which ended with the founding of the republic of the United States of America. The population was a mixed group of people—as were populations throughout New England. They had some loyalists, others who left for British territory (especially for Canada), and of course the Quakers who were non-combatants, leaving the remainder of the population ready and prepared to fight the British. It was claimed that, in fact, “Bristol county made the first actual war movements of the Revolution, a movement antedating the battle of Lexington by ten days.” [8, p. 98] A summary concluded that it is clear that “Bristol county as a whole exhibited active and unremitting loyalty to the patriotic cause in the struggle for freedom.” [8, p. 103] The whaling and shipping industries were stopped, leaving most without jobs, some of whom turned to privateering. Our ancestor, Lieutenant William Gordon, joined with Lieutenants Joseph Bell and James Metcalf, and Captain James Cushing, who commanded a detachment of an 80-man artillery. A few days before an anticipated invasion, they were called to take part in the Battle of Newport, Rhode Island, August 29, 1778, a battle noteworthy because “it was one of the first combined American-French military operations of the war, and that of the 1st Rhode Island Infantry, a brigade of composed a mixed racial element of European Americans, American Indians, and many African Americans, saw action.” [12]

Fresh from the R.I. battle, a part of the artillery company, under the command of Lieutenants Gordon and Metcalf were apprised of the landing of the British at Clark’s Cove, when they were in the vicinity of Caleb Russell’s house.

Howland provides color to this brief battle [9, pp. 68-69].

As this small detachment of our brave forces with its one mounted gun drawn by a yoke of oxen were forced northward on the County road, now Acushnet avenue, they were rapidly reinforced by volunteers from Acushnet, Freetown and the north end of New Bedford, and these home defenders that dreadful night made to the advancing host of 4,000 the strongest possible showing of their number, power of resistance and courage.

This demonstration of valor and patriotism encouraged Captain Cushing and his Lieutenants, Metcalf and Gordon, to decide to make a bold stand at the village bridge and resist an attempt by the enemy to cross the river and invade the “sacred soil” of Acushnet. This proposition met with the brave, enthusiastic approval of the numerous heroes that had gathered there to drive back the advancing foe—a hopeless task.

Captain Cushing ordered the bridge torn up and in various other ways prepared for an engagement of the enemy, which was slowly advancing in the moonlight. …

It is my belief that at this point, at the midnight hour of Saturday, September the fifth, 1778, a bloody battle was fought.

Our County and Its People [8, p. 322] adds succinctly, “At the Head-of-the-River Metcalf was mortally wounded, died three days later, and was buried in Old Acushnet Cemetery.

From this same source [8, pp.103-104] we also read that

The most important event that took place in the country during the war, was the invasion and destruction of Dartmouth on September 5, 1778 … The whaling industry, which employed fifty vessels in 1775 at New Bedford alone, was hopelessly crippled, settlements were destroyed, trade, manufacturing establishments and shipping burned, and settlers killed.

Further destruction of property is discussed [9, Chapter XXII]. The Revolutionary War is discussed in [9, pp. 63-78] and the information of individual soldiers of Acushnet, of which Bedford was then part, are discussed in some detail in [9, pp. 186-191].

Sarah, of specific interest to our ancestors is the story of Stephen and Abigail Hathaway and the British. The house of Stephen and Abigail Hathaway is described as “is one mile below Acushnet village, on the east side of the river.” [13, p. 186] In [8, p. 323] we read the following.

After establishing their destructive work at Acushnet the enemy proceeded down the road to Fairhaven. The first house destroyed was that of Col. Edward Pope [a fourth great granduncle of mine], a prominent and loyal citizen. Next the house of Stephen Hathaway [a second cousin six times removed of mine] was entered and the soldiers demanded money and valuables. When these were not forthcoming, they proceeded to search the house, forcing open desks and drawers with their bayonets and carrying away property. While these operations were in progress the commander-in-chief rode into the yard, and to him Mrs. Hathaway [née Abigail Quincy Smith] complained of the actions of the soldiers. He assured that it was not his intention to have any of the Friends disturbed and ordered a guard for the house. While there is no doubt that it was the policy of the British to leave the Quakers unmolested, it is still true that many were still maltreated.

Ricketson repeats this story [13, p. 295] giving credence to the facts related and adding a brief discussion of Thomas Hathaway and his ward, Jonathan Kempton, living with him. Two pages later, there is a brief but telling presentation of the British and their interactions with Stephen’s father, Jethro Hathaway [13, p. 297].

The British fell in with a Quaker, Jethro Hathaway, father of the [now] late Stephen; and took his broad-brim from his head, hurled it in the air, and after making much sport with it, said, ‘Let the old Quaker have it again’

It is interesting to see how these two accounts roughly corroborate the story that descendants of Stephen and Abigail added to the Hathaway holdings in the New Bedford Whaling Library. That will be presented and discussed in the Letter to Stephen and Abigail. Over time, it appears that the story may have morphed slightly yet continued to incorporate the salient details.

War of 1812

Although the war known as the War of 1812 essentially went from 1809 to 1815, an immediate cause was the war was a series of economic sanctions taken by the British and French against the U.S. as part of the Napoleonic Wars. In response to British actions of 1806, the U.S. first tried retaliatory embargoes which unfortunately had the effect of punishing the U.S. trade. As a result, the U.S. declared war against the British in 1812. It is not the intent to discuss this war in general but instead to focus on the effect on Acushnet and its immediate geographic area. For this we start with a description presented by Howland [9, pp. 88-90], a long-time resident and student of the local area. He published his book on the history of the area in 1907, writing it, presumably, in the late 19th and early 20th century, less than a hundred years after the war.

Acushnet was directly interested in and affected by the war with England in 1812. Many of the inhabitants of this town were engaged as agents, masters or seamen in the merchant marine and whale fishery at New Bedford, or in the many employments connected with these enterprises. This brought them in close touch with this unfortunate affair. It forced many of them into idleness and many of the families into almost suffering for the necessities of life. The proclamation issued by our national government in 1807 placing an embargo on shipping at all American ports, thus forbidding exports from this country, and the piracy of England on our shipping seriously affected the maritime interests of the Acushnet river. At this date sixty vessels were registered at the custom house belonging to the port of New Bedford. War was declared June 18, 1812. …

The work of preparing for the defense of the town began at once. Capt. William Gordon of Acushnet of Revolutionary War fame, superintended the construction of a mud fort on Love rock, just east of Fort Phenix, and a similar defense at Smoking rock near the location of the present Potomska cotton mills ate New Bedford. …

Remembering the fateful surprise given us by the British in the Revolutionary War, our people were determined New Bedford should not have a similar experience this time. To prevent this the coast was carefully and constantly guarded with an ample force. To prevent this the coast was carefully and constantly guarded with an ample force. Two companies were furnished for this purpose from the east side of the river, the “Fairhaven company” and the “Head-of-the-River company.” …

The end of this terrible war came with the signing of the treaty of peace at Ghent on Christmas eve, 1814, Our country had suffered a loss of 30,000 lives and $100,000,000 in the two and a half years of ware and gained absolutely nothing. The news was received with tremendous enthusiasm.

Another window into the effect of the war is offered in Our County and its People [8, pp. 341-342].

The closing of the port to all traffic in 1813 caused great inconvenience and suffering In order to supply the necessities of the inhabitants the so-called “Wagon Brigade” was established, and out from the seacoast villages processions of loaded vehicles went and came, making the journey sometimes as far as Albany. This method of obtaining supplies, which was unique for New Bedford, gave rise to considerable newspaper raillery. … These and very many similar announcements in the press would be intensely amusing, were it not for their pathetic foundation.

William Gordon continued to be active in New Bedford, and we note he taught at one of the schools [9, p. 121] and with his son leased and ran a wool carding mill, as seen in an advertisement in the New Bedford Mercury [9, p. 173].

Civil War

The Civil War was the most significant war since the Revolutionary War, and James Geary, quoted in Mulderink (14, p. 59] observed that “the Civil War represented a watershed between the transition from localism to the nascent nation-state.” Mulderink is an invaluable resource for New Bedford and its engagement in the Civil War, writing that [14, p. 5]: “Like other northern communities, New Bedford supported and shaped a national victory by the Union in significant ways that went beyond sending men off to military service.” He picks up on this theme specifically citing the efforts of both women and the defense of the coast [14, p. 54], describing the

martial spirit pervaded New Bedford as women began raising funds for departed troops and meeting publicly at City Hall to sew clothing. …From the first sign of war, the city’s generosity and alacrity in responding to the challenges of war remained a source of great civic pride …As the war unfolded, New Bedford responded in two principal ways: first, by actively recruiting soldiers and sailors, and second, by defending their home front against feared Confederate naval attacks.

And we learn [14, p. 57] that “By the war’s end, nearly 3,000 men were credited to New Bedford as soldiers and sailors, or 1,110 more than were required by the state thanks to the allowance of naval enlistment credits.”

Sarah, to date I have no information on close family members who fought in the war—perhaps due to age, perhaps to religion, although the following story, again related by Mulderink [14 p. 77], suggests that some Quakers approached the saving of the country differently. William Logan Rodman—a very distant relation of ours—

was New Bedford’s most prominent casualty during the Civil War. His military experiences and exalted death illustrate the tragic and transformative nature of the war and its multiple impacts on the home front. Rodman, a Quaker from old whaling wealth, was transfigured by the war, his personal and political beliefs shaped by changing events and opportunities for leadership and demonstrations of manly courage.

When I write to Humphrey Hathaway Swift (1819-1911), I will discuss his role in what I term pre-Civil War support for the north and include as well, some of his other activities in Brazil.

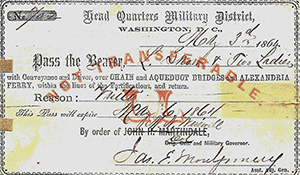

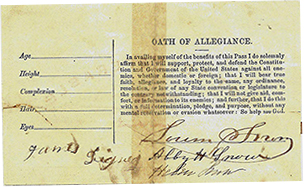

There is one last item from the time of the Civil War that needs mentioning and that relates to penciled comments Agatha added around 1942 to the 1860s carte de visit album. Here she writes that Grandpa Snow and Captain Hathaway went south during the Civil War. She also mentions a permit (to pass Union lines). I can note that a permit to pass into Washington, D.C., is in the family papers. Yet this permit is for Loum Snow (aka Grandpa Snow), his wife, Abbie, and their daughter, Helen. From [3, pp. 60], we see the story as we know it today.

The permit reads Pass the Bearer L Snow and two ladies with conveyance and driver over CHAIN and ACQUEDUCT BRIDGES and ALEXANDRIA FERRY, within the lines of the Fortification and return. REASON: Visiting.” The pass is dated May 3, 1864, and states that it will expire May 6. The back bears the signatures of Loum Snow, Abbie H. Snow. and Helen Snow. Did Agatha misremember Helen rather than Susan as the daughter? Was Grandma Snow (Abbie Harris Easton Mowry Snow) also part of the trip? Was there another pass for the Hathaways? Or were there at least two occasions for Grandpa Snow to go behind the lines? Considering the pass that we do have, we learn from a time line of the Civil War in May 1864 that on May 4 the final Spring Campaign of the Civil War began as the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan River in Virginia, and three smaller armies (those of Ohio, Tennessee, and Cumberland) pushed deeper into Georgia, and, on this date, the radical Wade-Davis Reconstruction Act passes in the U. S. House; one of its provisions was that the states who rebelled would need to be readmitted to the Union. And on May 5, “the Union Army of the Potomac once again locked horns with the Army of Northern Virginia in the dense thickets known as the Wilderness of Spotsylvania. Over the course of two days, the two armies fought to a bloody stalemate, inaugurating a new era of violence in the war in the East.” [15]

While we cannot verify the story related by Agatha of the Snow and Hathaway trip, as mentioned the family does have the actual pass for the May 1864 visit. While we have no documented reason for why Loum Snow took his wife and one daughter to Washington, D.C., there is the possibility that they were visiting a wounded soldier. We have no records of relatives who may have fought in the Civil War nor any record that Helen was engaged although this is possible. Moreover, we have no record that Isabel, her sister, was engaged, only learning of this, Sarah, through your records of objects. Since Susan and Helen were both your sisters-in-law, was this story not discussed at some time? Would that you could answer.

Citations

[1] Ancestry.com. Fifty New England colonists and five Virginia families [database on-line]. Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2004. Original data: Weiland, Florence Black, Fifty New England colonists and five Virginia families. Boothbay Harbor, Me., Printed by the Boothbay Register, 1966.

[2] Although there is no direct record of the senior Hunt’s arrival, it is believed that he traveled with his wife and son. The son is recorded as arriving in 1654 and they are known to have been in Newport at that time. See Colket, Meredith B., Jr. Founders of Early American Families: Emigrants from Europe, 1607-1657. Cleveland: General Court of the Order of Founders and Patriots of America, 1975.

[3] Frozen in Time, an early carte de visite album from New Bedford, Massachusetts, Second Edition, 2021, Susan Snow Lukesh.

[4] Agatha! Agatha Snow Abroad: A Sketch Book from her 1912 European Tour, 2020, Susan Snow Lukesh.

[5] “Starting with a Bracelet and a Family Tree: How Family Artifacts Inspired and Informed My Genealogical Search,” Susan S. Lukesh, American Ancestors, Summer 2013: 44-46.

[6] A History of Genealogy in America, François Weil, Harvard University Press, 2013.

[7] More on Elizabeth, her husband, and family as well as discussion of her as the first white female born in the early colony can be found in the following sources.

- Mayflower Families Through Five Generations, Volume 16 Part 1, Family of John Alden, General Society of Mayflower Descendants, 2000.

- Ancestry.com. Elizabeth (Alden) Pabodie and descendants [database on-line]. Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2005.

[8] Our county and its people : a descriptive and biographical record of Bristol County, Massachusetts Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2005. For more on the Revolutionary War and New Bedford, see www.whalingcity.net/new_bedford_local_revolutionary_war_1778.html

[9] A history of the town of Acushnet, Bristol county, state of Massachusetts, Franklyn Howland, Nabu Press (2010). For more on the War of 1812 and New Bedford, see www.whalingcity.net/new_bedford_local_history_1800%20-%201819.html

[10] First Generations: Women in Colonial America, Carol Berkin, Hill and Wang (1997).

[11] Jacob Schieffelin (1757-1835), Susan S. Lukesh, German Historical Institute, Immigrant Entrepreneurship Project, 2012.

[12] American Battlefield Trust; https://www.battlefields.org/learn/revolutionary-war/battles/rhode-island].

[13] The History of New Bedford, Bristol County, Massachusetts: Including a History of the Old Township of Dartmouth and the Present Townships of Westport, Dartmouth, and Fairhaven, from Their Settlement to the Present Time, Daniel Ricketson, Nabu Public Domain Reprints. Originally published by the author in 1858.

[14] Mulderink, Earl F., New Bedford’s Civil War, Fordham University Press, 2012.

[15] For the brief description of the Battles of the Wilderness see http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/the-wilderness.html. Accessed July 2, 2021.