Backstory:

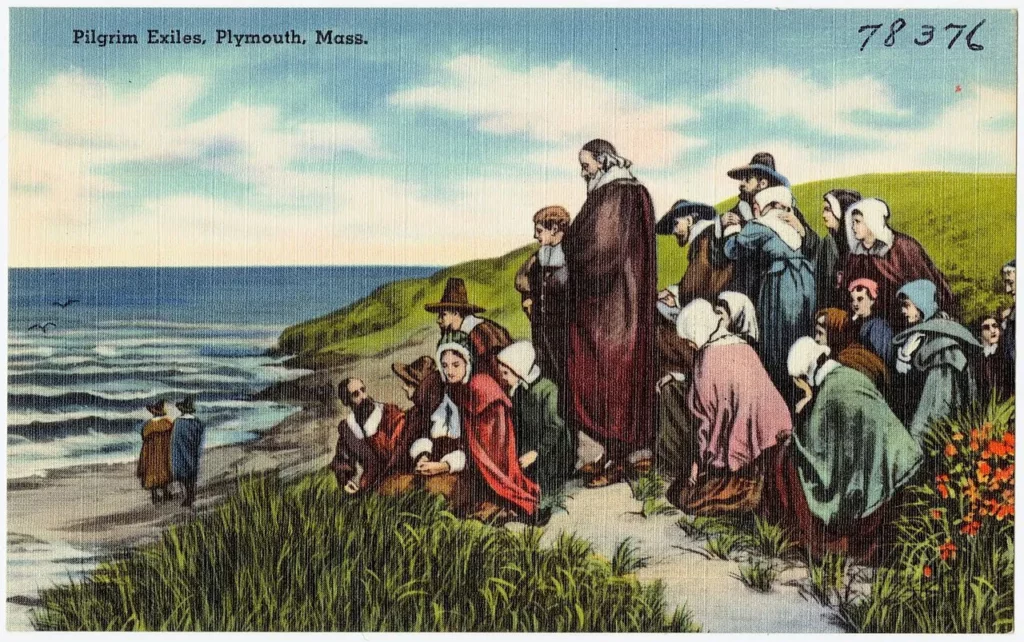

With 2,048 9th great grandparents and 1,024 8th great grandparents, how can we begin to make sense of our history? By writing letters to some of those who arrived in the early 17th c. in what would become the United States in less than two centuries. These letters remind them where they came from and tell them of the stories of their family that followed over subsequent the generations.

In the early stages of a large project that involves researching my ancestors who arrived in the 17th century, their descendants, and their intertwined lives [1] [2], I added studying creative non-fiction, where one suggested exercise was to write a letter to someone now deceased. this suggestion recalled for me the Ancient Egyptian practice of writing letters to the dead [3]. I knew immediately who it would be and so I composed a letter to my 3rd great grandfather, Henry Taber, available now as part of this project. Subsequently, as I move forward with this project, I am drafting letters to other ancestors whose story warrants a preliminary approach to their inclusion in the larger work. For me, these letters provide a gateway to this new project. For a reader, these letters may provide continuing interest in one of the many extended families, in this instance, one whose roots were planted in the 17th century in what would become the United States in the late 18th century.

Our ancestors, both direct and collateral descendants, are part of what I call the streams and rivers of people flowing together over time in our extended families; some of their prepared lineages can be accessed here. They are the tributaries or contributories to our extended family and similar to those of other extended families. Subsequent ancestors may have known much of our early history or perhaps never heard of it. Papers that my great grandmother, Sarah Gordon Hunt Snow collected, and much work undertaken by 20th and 21st century ancestry or family history studies, show a large number of families of ancestors in the extended family under consideration in southeastern Massachusetts, coming together, joining and then moving on, with future generations of these families rejoining, just as streams over time rejoin the tributaries from which they were born. One example of this is clearly seen in the lineages of the Coggeshall and Easton families. And it is possible to extend the idea of families as tributaries or contributories into a larger picture of floodplains built up by deposition creating fertile soil. With families rather than actual streams and rivers, the deposition is not for agricultural production but became fertile ‘soil’ for the development of the United States.

Thich Nhat Hanh, Buddhist monk and activist, has another complementary view expressed in his book Present Moment Wonderful Moment:

“If you look deeply into the palm of your hand, you will see your parents and all generations of your ancestors. All of them are alive in this moment. Each is present in your body. You are the continuation of each of these people.”

Subsequent ancestors may have known much of our early history or perhaps never heard of it. Papers that my great grandmother, Sarah Gordon Hunt Snow collected, and much work undertaken by 20th and 21st century ancestry or family history studies, show a large number of families of ancestors in the extended family under consideration in southeastern Massachusetts, coming together, joining and then moving on, with future generations of these families rejoining, just as streams over time rejoin the tributaries from which they were born. One example of this is clearly seen in the lineages of the Coggeshall and Easton families. And it is possible to extend the idea of families as tributaries or contributories into a larger picture of floodplains built up by deposition creating fertile soil. With families rather than actual streams and rivers, the deposition is not for agricultural production but became fertile ‘soil’ for the development of the United States.

These letters will present the actions of the men and women of this one of many large extended families, and the stories of women will not simply focus on their efforts in raising children, keeping the families well fed and supporting their fathers, husbands, and sons. [4] I was struck by the opening lines of a recently published Joy Harjo poem [5]

”In the lands of forgotten memories/I hear a woman singing”

and feel driven by the songs the women of these extended families sing to me over the centuries as I work to restore some of the forgotten or misplaced memories. And my interest in this extended family complements what I did in archaeology—birds of a feather although with different feathers—prehistoric archaeology and centuries of family history joined closely by a strong interest in restoring some of the past. In my senior year of high school, I was writing a senior paper on three WW1-era poets and in another class reading Russian literature in translation. In the second class I found these short couple sentences from Yevgeny Yevtushenko [6]:

“We who knew our fathers

in everything, in nothing.They perish. They cannot be brought back.

The secret worlds are not regenerated.”

And so I wrote a poem, My Mother’s Mother, in defiance of Yevtushenko’s statement, a poem that was inspired by my grandmother’s recounting of an early incidence in her life when her father woke her to watch ‘untamed geese, arrow-strict, divide the night.‘ Although an early school-girl poem, I published it in the Epilogue to Agatha! Little did I know when I wrote it that I would work to restore past lives throughout my life.

Recently, I read a letter that Ted Hughes sent to his son [7] closing with this line, which speaks directly to what I am attempting:

“And as the old Greeks said: live as though all your ancestors were living through you.”

I close these thoughts with a few lines that offer an image of what could be my ancestors over the centuries [8].

People had lived and died in this little village for hundreds and hundreds of years. I felt them suddenly, long lines of them reaching back through time, and let my hand capture that emotion in an easy sketch, figures in all manner of dress moving through and around each other, their feet crisscrossing the same paths. The quiet square seemed busy with their ghosts, their stories, and it made me feel peaceful in some arcane way.

And so, I write these letters as though my ancestors are living with or through me now. And I see them moving through the streets of the village and hear them murmuring while I strain to see and hear them more clearly so I can tell their stories.

I hope readers will take away the importance and value of both family and history, as well as, crucially, the part of the family in history.

——————————————

[1] From Malcolm Gaskill’s Between Two Worlds, How the English Became Americans., Basic Books, 2014, we read (p. 22),

From Jamestown’s vexed beginnings, to the failure of Sagadahoc [Maine, see pages 3-6], would-be adventurers and investors had learned three things, and they took that knowledge with them in the next phase of pursuing their American ambitions.

[2] Explorations of and even settlements in North America did not start in the 17th c. Roanoke’s settlement began in the later 16th century and within a few years the settlers were gone, how and where unknown; Jamestown and the Barbados, were established in the first decade of the 17thc century, and Plymouth of course was the first settlement to survive. These four were explored by Kathleen Donegan in Seasons of Misery, Catastrophe and Colonial Settlement in Early America, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014. In her introduction, Donegan wrote (p. 16],

In each case, I am interested in the period of settlement before the organization and stabilization of self replicating colonial societies. Over the course of the seventeenth century, colonies in New England, the Chesapeake, and the Caribbean were consolidated around different social, religious, economic, and racial systems, which profoundly shaped not only their cultural practices but also their religious identities.

[3] From The World History Encyclopedia, https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1051/letters-to-the-dead-in-ancient-egypt/ Accessed Oct 14, 2023.

The question of what happens after death has been addressed by religious beliefs and philosophies of every world culture throughout recorded history and ancient Egypt is famous for its own response to the mysteries of the afterlife. Their monumental tombs and temples are well known but a practice far less noticed is their letters to the dead. …

In ancient Egypt, however, the afterlife was a certainty throughout most of the civilization’s history. When one died, one’s soul went on to another plane, leaving the body behind, and hoped for justification by the gods and an eternal life in paradise. There was no doubt that this afterlife existed, save during the period of the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE), and even then the literature which expresses cynicism toward the next life could be interpreted as a literary device as easily as a serious theological challenge. The soul of a loved one did not cease to exist at death…

[4] Sources for women in the 17th century include

- The Women who Came on the Mayflower, Annie Russel Marble, Read & Co., 2020. (Originally published in 1920).

- Women’s Roles in Seventeenth Century America, Merril D. Smith, Greenwood Press, 2008.

- Weaker Vessels. The Women and Children of Plymouth Colony, American History Press, 2021.

[5] From “Sundown Walks to the Edge of the Story,” Joy Harjo, The New Yorker, May 9, 2022, p. 66.

[6] From “People” published in Yevtushenko: Selected Poems, Penguin UK, Jun 26, 2008.

[7] Letter “To Nicholas Hughes [Undated 1986]” from Letters of Ted Hughes selected and edited by Christopher Reid. Letters © 2007 by The Estate of Ted Hughes. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

[8] O’Neal, Barbara. The Art of Inheriting Secrets: A Novel (p. 80). Lake Union Publishing. Kindle Edition.

______________________________________________

Draft Letters Available

Francis Cooke (1583-1663)

and Philip Delano (1583-1663)

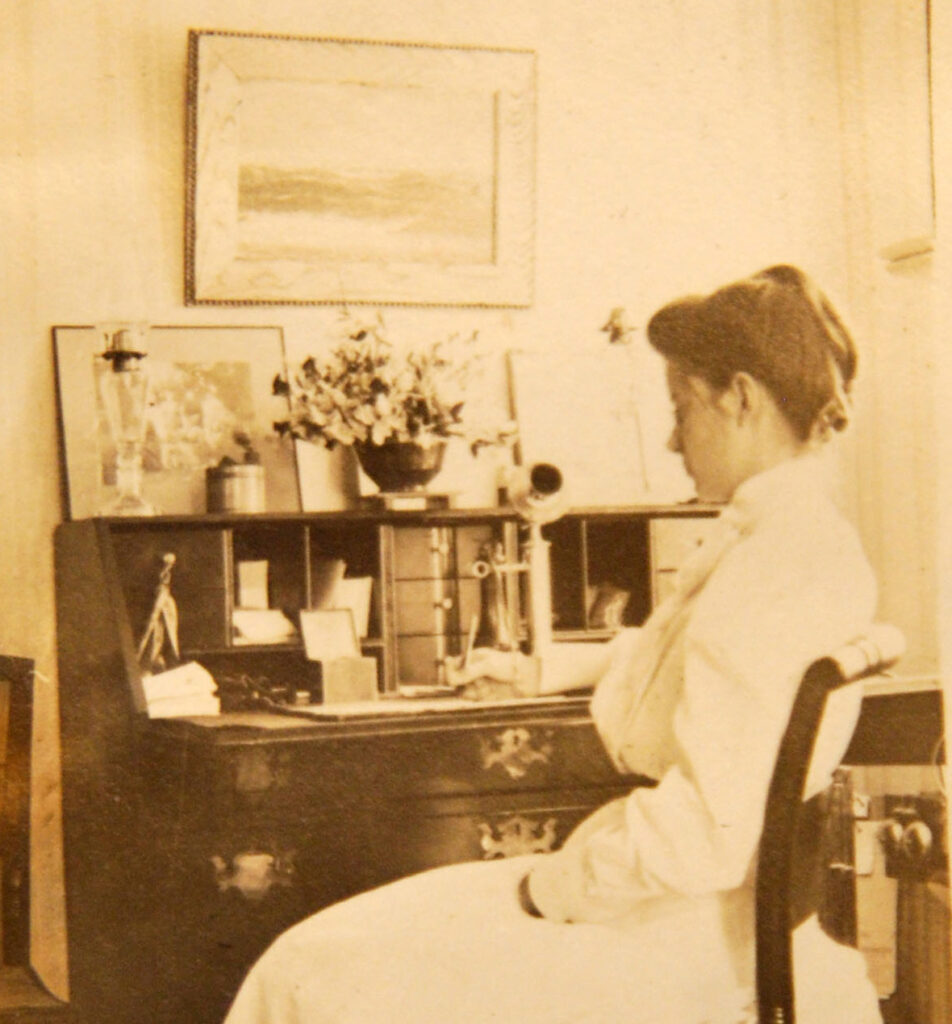

Sarah Gordon Hunt Snow (1860-1942)

Letters Planned

Constance Hopkins (1606-1677)

Jireh Swift(s) (1665 … 1965)

Abigail (1743-1831) and Stephen Hathaway (1743-1825)

Loammi/Loum Snow (s) (1779 … 2004)

Humphrey Hathaway Swift (1819-1911)

Abby Taber (1824-1906)

Horatio Hathaway (1831-1898)

Agatha Snow (1886-1963)

Deborah Snow Simonds (1921-2015)

These are the latest “Letters to My Ancestors”:

- Grandpa Francis Cooke and Cousin Philip DelanoDear Grandpa Francis and Cousin Philip: I am writing to you to introduce the legacies you have left in the close to 400 years since you arrived separately on the shores of North America—you, Grandpa, traveling with your oldest son, arriving on the Mayflower, and you, Cousin, traveling with your mother on the Fortune and arriving

- Dear Grandmother SarahMay 22,2022 Version 2 (August 24, 2022) Dear Grandmother Sarah, I recently wrote a letter to your grandfather, Henry Taber, my 3rd great grandfather, and the father of your mother Abby Taber. Very recently I found some interesting information I hadn’t known about our family’s much longer-term connection to Little Compton. You may well have known

- Dear Grandpa HenryPlease excuse the informality—I write from the 21st century where life is much less formal. For some years I have had a small photograph of the wonderful oil portrait of you near me and wished so often we could speak. As I explore more about our extended family, I’ve been given an exercise that suggests I write to someone with whom I cannot speak. So, I took up the challenge.